By Elizabeth Porter

Midnight Album Leaks and the DMCA

Taylor Swift’s 10th studio album, Midnights, was scheduled to release on October 21, 2022, but when fans got their hands on the physical album days before the planned release, copies of the songs started to appear on the internet. When song recordings are posted publicly without the artists consent, it is colloquially known as a “leak.” These “leaked” songs can be low-quality recordings of an early unmastered version of the song, or a phone recording of the physical album playing. A leak can usurp artist autonomy by either preempting a scheduled release date or releasing music that was never intended to be released. The artist, or label themselves, can also leak music without the consent of the other party for various reasons including marketing and disagreements between the parties.[1]

Swift is no stranger to album leaks. The first recorded time her album leaked was when her 4th album, Red, was leaked in its entirety.[2] After her 5th studio album, 1989, leaked on Tumblr, Swift addressed the situation with the following comment:

‘Two days before the album came out, it leaked online, and it was the first time I’ve ever had an album leak without it trending on Twitter — because my fans protected it,” she said. “Anytime they’d see an illegal post of it, they’d comment, ‘Why are you doing this? Why don’t you respect the value of art? Don’t do this. We don’t believe in this. This is illegal. This isn’t fair. This isn’t right.’ And it was wild seeing that happen.’[3]

Some Twitter users who shared the leaked Midnights files reported receiving communications from Swift’s team saying they were being sued.[4] Others questioned whether the screenshots of communications were real and accused the leakers of fabricating the incident for internet “clout”.[5]

I reached out to the parties involved to confirm the veracity of the claims to no avail. Regardless of authenticity, these allegations raise interesting issues on copyright in the digital age. What are the current legal issues and regulations for internet piracy? What is best practice in terms of business strategy for responding to music leaks? If Swift seeks to enforce her rights against individual Twitter users who shared leaks, what is the likely outcome of a potential lawsuit? Regardless of legal outcome, what is the correct economic or moral outcome?

I. Overview of Current Laws and Regulations for Digital Copyright Infringement

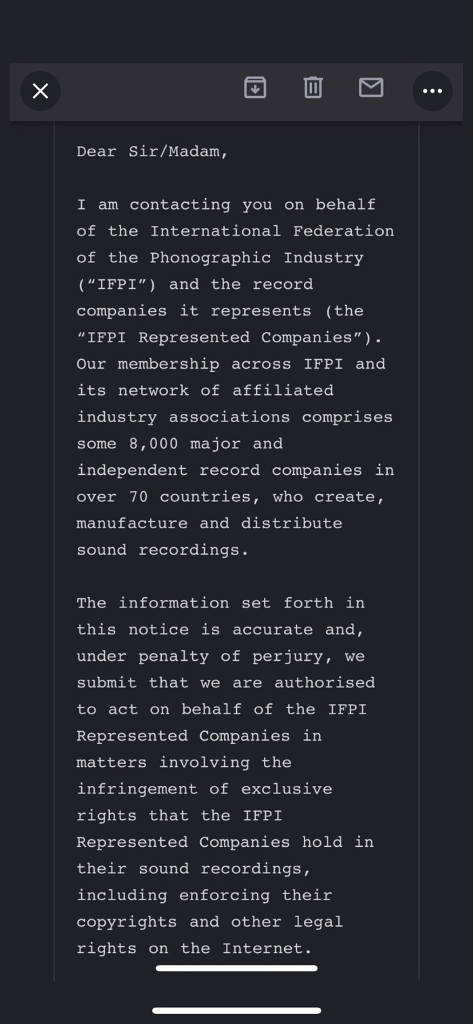

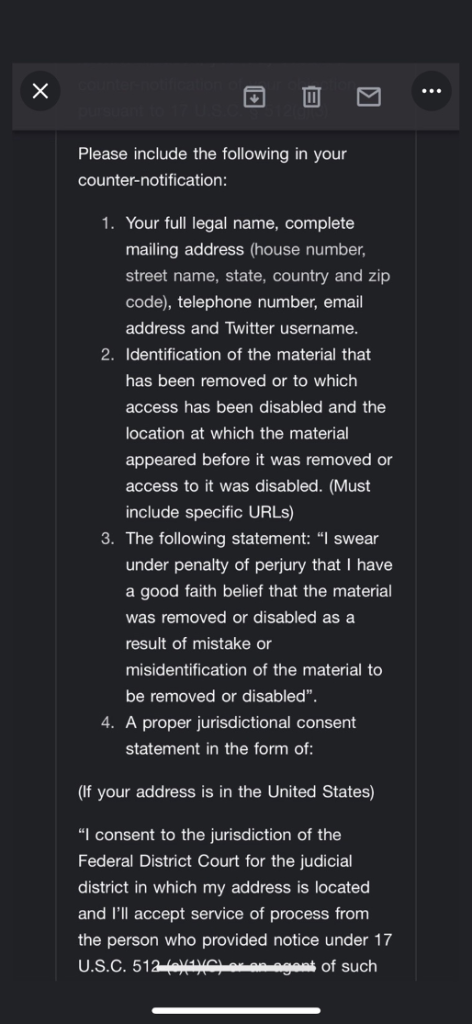

Based on the screenshots of the communications some users are providing (see attached figures), users are misrepresenting the nature of the communications, whether intentionally or out of confusion. The communications were not directly from Swift, her team, or her label. They also were not notice of a lawsuit. Essentially, the communications were sent in response to a takedown notice that Twitter received and is intended to inform the leakers why their content was removed and what they can do in response. The alleged communications appear to be sent on behalf of the record label by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (“IFPI”). The IFPI brands itself as “the voice of the recording industry worldwide” and its mission, in part, is “[T]o make sure that the rights of [their] members, who create, produce and invest in music, are properly protected and enforced.”[6] Swift’s current record label is Republic Records which is a subsidiary of Universal Music Group.[7] According to the IFPI website, Universal Music Group is one of their members.[8]

In the given communications, the IFPI is notifying the users of the counter-notification process they can pursue if they have a good-faith belief that their content did not infringe. The attached screenshots outline four pieces the users need to include in the counter notification: (1) personal identifying information, (2) links to the content and identification of what was shared, (3) a statement under penalty of perjury that the content was erroneously removed, and (4) consent to federal jurisdiction.

a. Digital Millennium Copyright Act §512(d): Notice and Take Down

The legalese contained in the IFPI communications that were allegedly sent to the leakers is confusing to the average internet user, but it is the standard operating procedure for internet copyright infringement. Where did this process come from?

Congress passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”) to “strengthen copyright protection in the digital age,” after concerns regarding the “ease with which pirates could copy and distribute a copyrightable work in digital form.”[9] DMCA Section 512(d) provides a safe harbor for internet service providers (ISP’s) to avoid indirect copyright infringement liability if they don’t have actual knowledge of infringing material on their platform.[10] The burden in the procedure weighs heavily on the copyright owner in this notice and takedown procedure. The copyright owner completes the “notice” part, and the “takedown” is completed by the ISP. This procedure requires the ISP to “upon notification of claimed infringement . . . respond[] expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material that is claimed to be infringing. . .” but the copyright owner has to identify the material, and provide direct links to the ISP.[11]

Once the copyright owner has notified the ISP of the infringing content, the ISP has to “expeditiously” remove the content. They will typically notify the user that the content was removed and inform them about the counter-notification process.[12] The counter-notification process provides recourse for users who did not infringe. If the user has a good-faith belief that they did not infringe, they can provide a DMCA counter notice to the ISP explaining the reason for their good-faith belief. If the ISP receives a counter notice, they are required to forward it to the copyright owner who provided the initial takedown notice. The copyright owner then has 10-14 days to file a suit against the user. If they fail to do so, the ISP must re-activate the alleged infringing content.[13] The alleged IFPI communications were intended to alert the leakers of the counter-notification process.

b. Business Strategy and Shortcomings of the DMCA

The DMCA notice and takedown procedure is operating as intended and is more efficient than the formal court system, but it is not perfect. From a business perspective, the notice and takedown measures are inadequate in part due to inefficiency.[14] The copyright owners must painstakingly identify all instances of infringement and provide the information to the ISP. They then have to wait for the ISP to review the alleged infringing content and remove it “expeditiously”. The word “expeditiously” is undefined and allows the ISP to wait hours and even days before removing content.[15] The longer that infringing content is left up, the more opportunity other wrong doers have to perpetuate harm by copying, and further sharing and distributing, the content. Due to these inefficiencies, copyright owners might have more incentive to target direct infringers (Twitter users/leakers).

Further, the DMCA process is simultaneously over and underinclusive. From the perspective of the user and the ISP, the process appears overinclusive. The ISP is required to remove content once they receive notice. They typically do not investigate whether the content actually infringes or whether there might be a defense, such as fair use, prior to removal. Instead, the DMCA attempts to cure wrongful removal with the counter notification process, described above, wherein the user can contest the removal. If they do, the ISP will reinstate the content but at this point, the content could have been down for potentially days or weeks. Things move fast on the internet and if content is erroneously removed, the user has likely missed the opportunity to comment on a current trend. If the ISP is consistently removing and suppressing user content, users may leave the platform in search of one that doesn’t remove their content. Thus, the counter notification process is unsatisfactory for users and ISPs.[16]

From the perspective of the copyright owner, the process is underinclusive. Because the copyright owner has the onus to identify and provide notice of each instance of infringement, a lot of infringing content gets left up. It’s expensive to identify infringement because it’s a time consuming and somewhat sophisticated endeavor. There is monitoring software that copyright owners can employ but technology is not perfect and doesn’t always flag all infringing content. YouTube, which is owned by Google, uses Content ID to flag content that might infringe and either remove it or monetize the video and give proceeds to the copyright owner.[17] The CEO of the IFPI has stated that the tool fails to identify 20-40% of their recordings.[18]

To illustrate this over-underinclusive conundrum, consider the following hypothetical. The YouTube Content ID tool flags a video from a channel that includes clips of popular music in videos where they review and discuss new music from a news and educational perspective. The tool does not flag a YouTube channel that posts popular music in its entirety with the song lyrics as the visual display. On this channel, they provide no additional commentary and leverage ads to monetize the content. In this case, the music review channel would likely fall under fair use and not infringe where the lyric video channel would likely not fall under fair use and would infringe. The process has over included the music review channel and under included the lyric video channel.

The DMCA attempts to balance inefficiencies by removing the process from the formal court system and thus not require copyright owners to bring a claim against each individual user and instance of infringement. But the process leaves all parties unsatisfied – except those who get away with infringing. What is the alternative? Perhaps it is time to review the DMCA and reconsider how we view digital copyright piracy. Currently, the only alternative is to use the formal court system which is more unwieldy and inefficient than the DMCA process.

II. Hypothetical Case Analysis: “Swift et al. v. Leakers”

If Swift, Republic Records, and Universal Music Group[19] choose to file suit against the direct infringers who go through the counter-notification process and swear under penalty of perjury that they have a good faith belief their content did not infringe, the issue will likely hinge on whether a fair use defense will apply.

The Copyright Act provides legal protection for “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression,” including sound recordings.[20] Copyright owners have the exclusive right to distribute and reproduce copies of such works and to perform those works via digital audio transmission.[21] A copy is a “material object . . . in which a work is fixed by any method now known or later developed, and from which the work can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.”[22] An individual commits copyright infringement by violating one or more of the exclusive rights of the copyright owner, such as sharing digital files online.

Some leakers are under the erroneous impression that because the music hasn’t been released, there is no copyright, and they can avoid liability. Publication in the form of releasing an album to the public is not a requirement to register a copyright and a creative work does not need to be registered before exclusive rights are established. Registration is only a requirement for enforcing one of the exclusive rights to a creative work. If something is minimally creative and fixed in a tangible medium, it is protectable.[23]

Fair use is the most common defense to a claim of copyright infringement.[24] The fair use doctrine balances the public benefit against the private interest of the copyright owner. Thus, a large part of the inquiry is whether there is a public benefit to the infringing content. The Copyright Act requires the court to consider four factors to assess whether the use is fair: (1) The purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyright work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work. [25]

The facts here likely weigh against fair use. Though Swift will have a hard time establishing that the leaks affected her market share and value, the first three factors weigh squarely against fair use.

Under the first factor, uses that are educational, non-commercial, parody, or transformative are typically considered “for the public benefit”, and weigh towards fair use. In contrast, if the purpose is commercial or non-transformative, the use has minimal public benefit and is likely not fair. The second factor is typically an inquiry of how creative the work is.[26] Here, the leakers purpose was not to educate the public or transform the original work in any way to provide the public with additional commentary or meaning. They merely shared the entirety of a song for the implied purpose of gaining social media engagement and clout in the form of likes, replies, and followers.

The fact that the songs were leaked likely helps Swift in this situation. In Harper & Row, the court explained that “. . . the scope of fair use is narrower with respect to unpublished works”[27] and when the infringer obtains the work through nefarious means for the purpose of, “supplanting the copyright owners commercially valuable right of first publication”, the purpose and character is not fair.[28] Thus, the fact that the songs were shared prior to publication likely weighs against fair use.[29] If the facts demonstrate that the files were obtained through nefarious means, such as hacking, rather than simply recording a legally obtained physical copy, this also would help Swift win this hypothetical case. Using the Harper & Row case as precedent, the court will likely find that because the album was not yet released, the purpose and character of the use is not fair.

Further, even though there is not an explicit commercial purpose in terms of a valuable exchange, the court can arguably find a commercial purpose in the form of social media clout. The lines between commercial and personal social media use grow blurrier each year. Social media influencing is a $16.4 billion global industry fueled by followers.[30] Each time someone posts on social media, that post has a chance of “going viral” and earning the user a substantial increase in followers. The number of followers a user has determines the value of paid content.[31] As such, depending on the user, any Tweet could arguably be for a commercial purpose.

Under the third factor, the question is how much of the original work was shared. Here, the users shared full songs in their entirety which makes the analysis simple and avoids the need to analyze the quality of the content that was shared. Because the users shared full copies of the songs with no changes or additions, the court will likely find that the third factor weighs against fair use.

Finally, because there is no evidence that the leaks affected her album sales, the fourth factor likely weighs in favor of fair use. Swift’s market share and value of the album are unlikely to be affected., in part because of her fame and star power.[32] In fact, this album has broken many records since release including being the first album to ever occupy the first ten spots on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.[33] If it was a different artist who was less well-known, the fact that the infringement occurred prior to release could potentially help establish that the market was effected but under these facts, Swifts star power likely outweighs any negative market effects. Swift is a shining example of an artist who has successfully connected with fans to create a form of brand loyalty. Because the fans are so loyal, they will continue to support her by buying physical albums.

Ultimately, the Twitter users almost certainly infringed, and a fair use defense will likely be unsuccessful because the purpose and nature of the use is not creative, transformative, or educational, and they shared a near exact copy of the sound recording prior to publication.

III. Economic Theory of Copyright Law

Is the likely legal outcome, against fair use, in line with the economic theory of copyright law? The economic theory of copyright law is that the laws should balance supporting public access to creative works against individual incentives to create the works. These two goals are at odds, but effective copyright laws balance these competing interests to most efficiently incentivize the production of creative works.[34]

Do leaks have an appreciable negative economic effect on the music business? Theoretically, when a potential buyer has access to a leak, they could be deterred from purchasing an album or streaming it legally, though this would be difficult to prove in court. You could imagine an attorney attempting to locate individuals who will testify that they were planning to purchase a song but changed their mind after they obtained access to a leak. Even if it would be difficult to prove what impact leaks have on the business, if any, streaming and purchasing of digital and physical music remains an important economic aspect of the industry.

Labels, publishers, streaming services, and other businesses in the industry, distinct from the artists, have a clear interest in maintaining the revenue stream from sales and streams. These business entities support artists and enable them to share their work publicly and earn a living while doing so. As such, it’s important to keep their interests in mind when considering changes to copyright laws and regulations. Because the music business at large has an economic interest in eradicating piracy, the probable legal outcome of the hypothetical case above would be correct under an economic theory of copyright law.

Is there an economic interest and incentive for the artist themselves? Contrary to popular belief, musical artists have always received a higher proportion of their income from touring, merchandising, and licensing rather than album sales or streaming.[35] This is partially because artists share streaming and album sale revenue with labels, songwriters, and publishers.[36]

From the perspective of a major musical artist, there is an economic incentive to eradicate piracy because they receive revenue from streams and music sales. But there may be less of an economic incentive for an artist compared to their record label because there is no indication that a potential increase in streaming or album sale revenue would have enough of an impact on their income to provide an impetus for more creative output. However, there may be more of a moral incentive for the artist, especially when the pirated music is a leak.

IV. Moral Goals of Copyright Analysis

United States copyright laws are largely based on the economic theory but other countries, like France, ground their copyright laws in terms of moral rights.[37] But over the past forty years or so, the United States has incorporated some theories of moral rights into our copyright laws.[38] One example is the right of public distribution. As discussed above, in Harper & Row, the Court held that “the author’s right to control the first public appearance of his undisseminated expression will outweigh a claim of fair use.”[39] This idea is expressed from the viewpoint of the authors moral right to control how the public first receives their work, rather than an economic right to maximize revenue after publication. The Court is recognizing the importance of artist autonomy and the role that personal expression plays in the creation of artistic works. Moral rights are more difficult to quantify than economic rights, but they are arguably more important to the goal of fostering artistic expression. Even without economic incentive, people will still create works of art, albeit there would be less artistic output. When artists are personally invested in their work and create from a place of vulnerability and intimacy, the public benefits. We want artists to be connected to their work in this way because the work is typically better. This is the inherently intangible quality of art that is emotionally moving to the consumer. It is what makes art valuable in non-economic terms.

Under a purely economic analysis, the idea of Swift suing her eighteen-year-old fans for sharing songs three days early, seems a silly endeavor for a celebrity with her level of success. However, from a moral rights theory, the success of the artist doesn’t matter, and the idea of this hypothetical lawsuit seems more appropriate.

Swift is a singer-songwriter and has solo songwriting credit on 54 songs and co-songwriting credit on the rest of the over 150 tracks she has released.[40] As such, Swift is intimately involved in the creation of each song and album. The lyrics, melody, and overall production are personal. She sings about her life, her experiences, and her feelings about those experiences in a deeply intimate and vulnerable way. To have this personal work be exploited for social media clout is likely extremely distressing to Taylor Swift.[41] In fact, when she was asked on the Alan Carr show how she would feel if her 1989 album was leaked she replied, “I don’t want to talk about leaks. It freaks me out. I will have a meltdown on the show.”[42]

Whether it is a pop star or an indie artist, under a moral theory of copyright music, leaks should never be fair use.

V. Conclusion

The probable outcome of the hypothetical case above is correct under both an economic and moral theory of copyright law. When artist autonomy is usurped for internet clout or explicit economic gain, the law should provide relief for copyright owners. Under the current fair use analysis, copyright owners should be able to enforce their rights. However, the vast majority of instances of copyright infringement will never see the formal court system because inefficiencies of the DMCA and formal court system.

The DMCA has shortcomings in terms of efficiency and ability to respond to all instances of infringement. But the nature of the internet is so fast paced that it provides a better alternative for copyright owners than the formal court system did previously. Though the DMCA is unsatisfactory in many ways, until Congress and lobbyists think of a better alternative, the notice and takedown procedure remains the best practice for copyright owners to respond to leaks.

One of the issues present in the Midnights album leak debacle was the lack of knowledge in copyright laws and regulations on the part of the leakers and twitter users more generally. If the leakers knew that they were breaking copyright laws, would they still have posted the leaks? Some probably would have but maybe others would have been deterred. Regardless, educating the public on copyright law specifically, and internet law more generally, would have a benefit in so far as knowledge is powerful.

As social media has grown and become an inexorable fact of life, questions of copyright law, and particularly fair use, have become more complex. Is fair use working as intended on the internet? Are influencers exceeding their rights under the fair use doctrine? Should ISP’s take a more active role in responding to copyright infringement? This presents exciting opportunities for legal scholars to research and propose new policy.

[1]Alexander Forsey, How Does Music Leak?, Opto Prods.,

https://www.optoproductions.com/how-does-music-leak/ (last visited Jan. 13, 2023). ; Gabe LaCagina, The Leaked Music Industry, Rap TV (May 23, 2021), https://raptv.com/editorials/the-leaked-music-industry/.

[2]Kelsey McKinney, Taylor Swift’s new album 1989 has leaked, Vox (Oct. 24, 2014, 5:52pm EDT), https://www.vox.com/xpress/2014/10/24/7061625/taylor-swift-1989-leaked-album-leak.

[3]Taylor Swift Says Her Fans Protected ‘1989’ After Leaks: ‘They Didn’t Spoil The Secret’, Music Times (Nov. 1, 2014, 12:42pm EDT),

[4] @t13_glossy_, Twitter (Oct. 19, 2022, 7:33am),

[5] Clout was previously understood to mean power or influence, but the definition has evolved to refer to digital cultural currency or relevancy. See Kaitlyn Tiffany, Why Kids Online Are Chasing ‘Clout’, The Atlantic (Dec. 23, 2019), https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/12/clout-definition-meme-influencers-social-capital-youtube/603895/.

[6] IFPI, https://www.ifpi.org/about-us/what-we-do/, (last visited Jan. 13, 2023).

[7] Brittany Spanos, Taylor Swift Signs with Republic Records and UMG, Her First New Home in 13 Years, Rolling Stone (Nov. 19, 2018), https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/taylor-swift-record-deal-republic-records-umg-757711/.

[8] IFPI, https://www.ifpi.org/members/our-members/, (last visited Jan. 13, 2023).

[9] Universal City Studios v. Corley, 273 F.3d 429, 435 (2d Cir. 2001).

[10] 17 U.S.C. §512(d).

[11] Id.

[12]The basics of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, Reps. Comm. for Freedom Press, https://www.rcfp.org/journals/news-media-and-law-winter-2012/basics-digital-millennium-c/#:~:text=It%20must%20then%20remove%20the,against%20the%20allegedly%20infringing%20subscriber, (last visited Jan. 13, 2023).

[13] DMCA Counter-Notice Process, Copyright All., https://copyrightalliance.org/education/copyright-law-explained/the-digital-millennium-copyright-act-dmca/dmca-counter-notice-process/, (last visited Jan. 13, 2023).

[14] Major Music Organizations Decry Broken DMCA, Outline Possible Solutions In New Government Filing, RIAA (Feb. 21, 2017), https://www.riaa.com/major-music-organizations-decry-broken-dmca-outline-possible-solutions-new-government-filing/.

[15]Id.

[16] G. Teran, Who is Vulnerable to Suit? Internet Service Provider Liability and Jurisdiction, Berkman Klein Ctr. for Internet & Soc’y Harv. U. (Feb. 2, 1999), https://cyber.harvard.edu/property99/liability/main.html.

[17] How Content ID Works, Google, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2797370?hl=en, (last visited Jan. 13, 2023).

[18] Tim Ingham, YouTube’s Content ID fails to spot 20%-40% of music recordings, Music Bus. Worldwide (Jul. 13, 2016), https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/youtubes-content-id-fails-spot-20-40/.

[19] Swift’s contract terms are not public knowledge, but Swift shared that with her new contract, she will own all of her masters and it is believed that she shares royalties equally with her label. See Abigail Freeman, Taylor Swift Is ‘Free’ Again, But Just How Much Is Her ‘Fearless’ Strategy Worth?, Forbes (Apr. 9, 2021, 01:05pm EDT), https://www.forbes.com/sites/abigailfreeman/2021/04/09/taylor-swift-is-free-again-but-just-how-much-is-her-fearless-strategy-worth/?sh=7ef731c17f05.

[20] 17 U.S.C. § 102(a).

[21] 17 U.S.C. § 106.

[22] 17 U.S.C. § 101.

[23] Id.

[24]Richard Stim & Brian Farkas, Fair Use: The Four Factors Courts Consider in a Copyright Infringement Case, Nolo, https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/fair-use-the-four-factors.html#:~:text=If%20someone%20comes%20along%20and,to%20claims%20of%20copyright%20infringement, (last visited Jan. 13, 2023).

[25] 17 U.S.C. §107.

[26] Id.

[27] Top of Form

Harper & Row, Publrs. v. Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 564 (1985).Bottom of Form

[28] Id. at 563.

[29] See id.

[30] Werner Geyser, The State of Influencer Marketing 2022: Benchmark Report, Influencer Mktg. Hub (Mar. 2, 2022), https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/.

[31]Joel Mathew, Understanding Influencer Marketing And Why It Is So Effective, Forbes (Jul. 30, 2018, 08:00am EDT), https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2018/07/30/understanding-influencer-marketing-and-why-it-is-so-effective/?sh=3377bda471a9.

[32] There is a market for unreleased songs. See Gabe LaCagnina, The Leaked Music Industry, RapTV (May 23, 2021), https://raptv.com/editorials/the-leaked-music-industry/.

[33] Gary Trust, Taylor Swift Makes History as First Artist With Entire Top 10 on Billboard Hot 100, Led by ‘Anti-Hero’ at No. 1, Billboard (Oct. 31, 2022), https://www.billboard.com/music/chart-beat/taylor-swift-all-hot-100-top-10-anti-hero-1235163664/.

[34] William M. Landes & Richard A. Posner, An Economic Analysis of Copyright Law, 18 J. Leg. Stud. 325, 325-33, 344-53 (1989).

[35] Devon Delfino, How musicians really make their money — and it has nothing to do with how many times people listen to their songs, Bus. Insider (Oct. 19, 2018, 11:59am),

https://www.businessinsider.com/how-do-musicians-make-money-2018-10.

[36] Id.

[37] 3 Nimmer on Copyright § 8D.

[38] Id.

[39] Harper & Row,471 U.S. at 555.

[40] Danielle Pascual, Here’s Every Song Taylor Swift Wrote On Her Own, Billboard (Jan. 25, 2022),

https://www.billboard.com/music/pop/taylor-swift-solo-songwriter-list-1235022983/.

[41] Oakley Burt, Pop-Cultured: The Morality of Leaked Music, Daily Utah Chron.(Apr. 17, 2020), https://dailyutahchronicle.com/2020/04/17/pop-cultured-morality-leaked-music/.

[42] Rosalyn Oshmyansky, Taylor Swift Said She’d Have a Meltdown If ‘1989’ Leaked and It Did, ET (Oct. 25, 2014, 11:12am PDT), https://www.etonline.com/news/153060_taylor_swift_said_she_would_have_a_meltdown_if_1989_leaked_and_it_did.

Figure 4